Người Nhật lịch thiệp nhất thế giới?

Steve John Powell và Angeles Marin Cabello- 28 tháng 5 2016

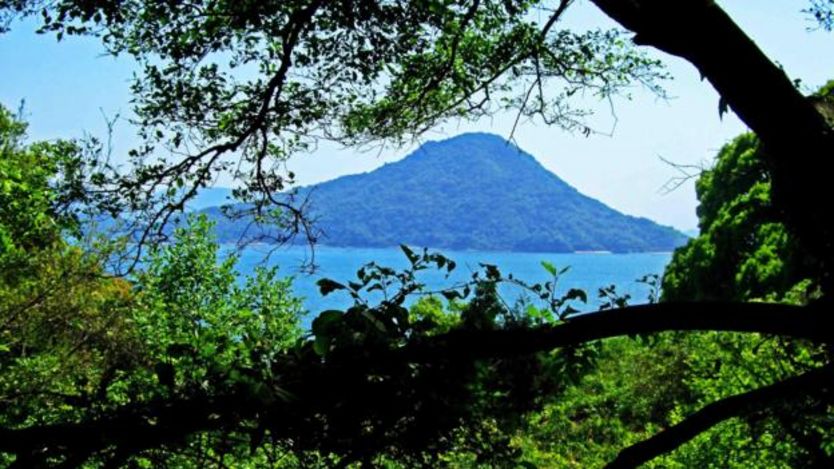

Mặt trời đã bắt đầu lặn xuống mặt biển ánh đỏ báo cho chúng tôi biết là chúng tôi đã nấn ná đạp xe quá lâu trên đảo Ninoshima tại vịnh Hiroshima, Nhật Bản. Không chắc chắn về việc rời bến của chuyến phá cuối cùng đi vào đất liền, chúng tôi đứng lại hỏi ở một quán bên đường. Việc này làm nhiều người lo lắng vì chuyến phà sắp rời bến.

"Các anh sẽ kịp nếu đi theo đường tắt" một người bước ra ngoài nói, anh chỉ về phía một con đường hẹp đi lên đồi. Do trời đang tối đi rất nhanh nên chúng tôi rất nghi ngại nhưng rồi cũng đạp xe lên dốc. Khi nhìn quanh chúng tôi ngạc nhiên thấy anh bạn vừa mới gặp chạy bộ sau chúng tôi với một khoảng cách tế nhị để đảm bảo chúng tôi không bị lạc đường, và chỉ quay lại khi bến cảng xuất hiện ở cuối dốc. Việc làm tử tế ngẫu nhiên của anh giúp chúng tôi tới phà sớm vài phút.

Đó là một trong những trải nghiệm đầu tiên với omotenashi, thường được dịch là "sự mến khách Nhật Bản". Thực tế nó là sự kết hợp của sự lịch thiệp hết sức tinh tế với khát khao giữ hòa thuận và tránh xung khắc.

Omotenashi là một cách sống ở Nhật. Người bị cảm lạnh mang khẩu trang để tránh lây sang người khác. Người láng giềng đưa hộp bột giặt bọc gói như quà tặng trước khi bắt đầu việc xây dựng, ý là để bạn giặt quần áo vì thể nào cũng sẽ có bụi bậm.

Nhân viên các cửa hàng và quán ăn cúi gập chào đón bạn với câu nồng nhiệt irasshaimase (xin chào quý khách). Khi trả lại tiền thừa, họ đặt một tay dưới tay bạn để tránh rơi xu. Khi bạn rời tiệm, không có gì là bất thường khi họ đứng ở lối ra và cúi tiễn chào cho tới khi bạn đi khuất.

Kể cả máy móc cũng thực hiện omotenashi. Cửa xe taxi tự động mở khi bạn tới gần và găng tay trắng đồng phục của lái xe không chờ đón tiền boa. Thang máy xin lỗi khi làm bạn phải đợi lâu, và khi bạn vào nhà vệ sinh nắp bệ ngồi tự động bật lên. Biển báo trên đường 'có công trường phía trước' vẽ hình một công nhân xây dựng cúi chào rất ngộ nghĩnh.

Hàng xóm tặng hộp bột giặt được bọc gói đẹp đẽ (Ảnh: MIXA/Alamy)

Trong văn hoá Nhật, người càng là người lạ trong một nhóm nào đó thì càng được đối xử lịch thiệp, đó là vì sao người nước ngoài (gaijin, nghĩa là người ngoài) không thể không ngỡ ngàng thấy mình được quá ưu đãi. "Điều này vẫn làm tôi ngạc nhiên sau 9 năm ở đây," Carmen Lagasca giáo viên tiếng Tây Ban Nha nói. "Người ta cúi chào khi ngồi cạnh bạn trên xe buýt, và lại cúi chào khi đứng dậy. Lúc nào tôi cũng thấy cái gì mơi mới."

Nhưng omotenashi vượt trên cả việc đối xử tốt với khách; nó thấm sâu và lan tỏa ở mọi cấp bậc của cuộc sống hàng ngày và được giáo dục từ khi còn trẻ thơ.

Người Nhật học phép lịch sự từ một câu tục ngữ cổ (Ảnh: Alexander Spatari/Getty)

"Nhiều người trong chúng tôi lớn lên với một câu tục ngữ," Noriko Kobayashi, giám đốc công ty du lịch DiscoverLink Setouchi với mục tiêu tạo công việc, gìn giữ di sản địa phương và phát triển du lịch ở Onomichi, tỉnh Hiroshima, nói. "Câu tục ngữ đó là 'Sau khi ai làm điều gì tốt với ta thì ta nên làm điều gì đó tốt cho người đó. Nhưng sau ai khi làm điều gì xấu với ta, ta không nên làm điều gì xấu với người đó,' tôi nghĩ rằng suy nghĩ đó làm chúng tôi lịch thiệp trong cư xử."

Vậy tất cả sự lịch thiệp đó ở đâu mà ra? Theo Isao Kumakura, giáo sư danh dự ở viện nghiên cứu của Bảo Tàng Quốc Gia Dân Tộc Học ở Osaka thì phần lớn phép xã giao của Nhật bắt nguồn từ lễ nghi chính thức của nghi thức dùng trà và võ thuật. Thực tế là danh từ omotenashi, có nghĩa "tinh thần phục vụ", là xuất phát từ nghi thức dùng trà. Chủ nhà cố gắng hết sức để tạo không khí thích hợp để chiêu đãi khách, lựa chọn những bát, hoa và đồ trang trí phù hợp nhất mà không mong đợi bất kỳ điều gì từ khách cả. Khách biết chủ rất vất vả, đền đáp bằng cách thể hiện lòng biết ơn vô vàn. Cả hai bên tạo ra một không khí hòa hợp và tôn trọng, xuất phát từ lòng tin là cái tốt lành chung cho nhiều người phải đi trước nhu cầu riêng tư.

Người địa phương cúi gập chào đón bạn và niềm nở nói irasshaimase (xin chào) (Ảnh: Wayne Eastep/Getty)

Người địa phương cúi gập chào đón bạn và niềm nở nói irasshaimase (xin chào) (Ảnh: Wayne Eastep/Getty) Cũng tương tự như vậy, lịch thiệp và thông cảm là những giá trị cốt lõi của Bushido (Hiệp sỹ đạo) tức quy tắc đạo đức của samurai. Quy tắc tinh vi này, tương tự như phong cách hiệp sĩ thời trung cổ, không những chỉ chi phối danh dự, kỷ luật và đạo đức, mà còn cả cách làm đúng đắn mọi việc từ bắn cung đến pha trà. Lời giáo huấn dựa vào thiền của phong cách trên đòi hỏi biết làm chủ cảm xúc, tĩnh tâm và tôn trọng người khác kể cả kẻ thù. Bushido là nền tảng cho quy tắc cư xử nói chung trong xã hội.

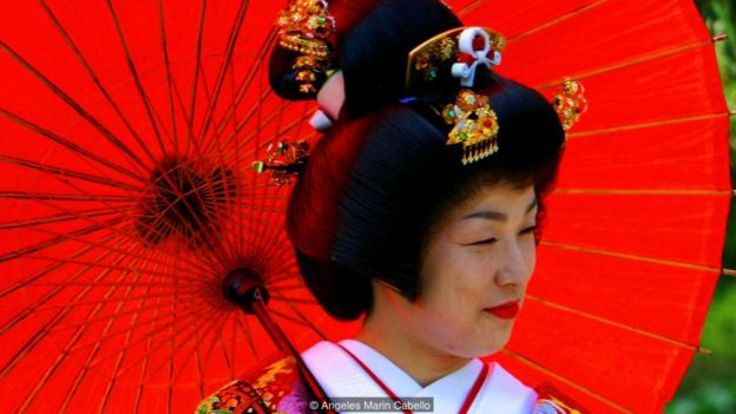

IỞ Nhật Bản sự lịch thiệp lan tỏa đến mọi mức độ của cuộc sống hàng ngày và được dạy bảo từ thuở còn thơ (Ảnh: Angeles Marin Cabello)

IỞ Nhật Bản sự lịch thiệp lan tỏa đến mọi mức độ của cuộc sống hàng ngày và được dạy bảo từ thuở còn thơ (Ảnh: Angeles Marin Cabello) Điều kỳ diệu khi tiếp xúc với biết bao điều lịch thiệp là nó có tính dễ lây như bệnh sởi. Chẳng bấy lâu mà bạn cảm thấy mình cư xử tốt hơn, nhẹ nhàng hơn, có ý thức trách nhiệm hơn, giao nộp ví người khác đánh rơi cho cảnh sát, mỉm cười khi nhường đường cho các lái xe khác, không vứt rác bừa mà mang rác về nhà và không bao giờ nói to (hoặc xỉ mũi) nơi công cộng.

Sẽ tuyệt vời không nếu mỗi người thăm Nhật mang một chút omotenashi về nhà và phân phát ra xung quanh? Hiệu ứng làn sóng có thể lan tràn khắp thế giới.

http://www.bbc.com/vietnamese/culture_social/2016/05/160528_the-worlds-most-polite-country_vert_tra

Daniel Doan* PaulaLe* Kimmy Nguyen

Daniel Doan* PaulaLe* Kimmy Nguyen|

|

The world's most polite country?It's so well mannered that even the toilet seat stands to attention when you enter the bathroom.

- By Steve John Powell and Angeles Marin Cabello

The sun had already begun dissolving into the reddening sea, an alarming reminder that we had dilly-dallied a little too long on our cycling jaunt round Japan's Ninoshima Island in Hiroshima Bay. Unsure of the ferry's last departure for the mainland, we stopped at a roadside bar to ask. This triggered worried looks all round: the final boat was about to leave.

Japan's Ninoshima Island in Hiroshima Bay (Credit: Angeles Marin Cabello)

"You can just make it if you take the shortcut," said one man, stepping outside and pointing to a narrow road up a small mountain. With evening falling fast, we had severe misgivings, but cycled off uphill nonetheless. Looking round, we were astonished to see our newfound friend jogging up the hill behind us at a discreet distance to ensure that we didn't get lost, only turning back when the port was safely in sight below us. His random act of kindness got us to the ferry with minutes to spare.

This was one of our first experiences with omotenashi, which is often translated as "Japanese hospitality". In practice, it combines exquisite politeness with a desire to maintain harmony and avoid conflict.

People bow outside of a shrine in Kyoto (Credit: Russell Kord/Alamy)

Omotenashi is a way of life in Japan. People with colds wear surgical masks to avoid infecting others. Neighbours deliver gift-wrapped boxes of washing powder before beginning building work – a gesture to help clean your clothes from the dust that will inevitably fly about.

Staff in shops and restaurants greet you with a bow and a hearty irasshaimase(welcome). They put one hand under yours when giving you your change, to avoid dropping any coins. When you leave the shop, it's not unusual for them to stand in the doorway bowing until you are out of sight.

Neighbours offer gift-wrapped boxes of washing powder (Credit: MIXA/Alamy)

Machines practice omotenashi, too. Taxi doors open automatically at your approach – and the uniformed white-gloved driver doesn't expect a tip. Lifts apologise for keeping you waiting, and when you enter the bathroom the toilet seat springs to attention. Roadwork signs feature a cute picture of a bowing construction worker.

In Japanese culture, the farther outside one's own group someone is, the greater the politeness shown to that person – which is why foreigners (gaijin – literally, "outside people") are invariably astounded to find themselves accorded such lavish courtesies. "It still surprises me after nine years here," said Spanish teacher Carmen Lagasca. "People bow when they sit next to you on the bus, then again when they get up. I'm always noticing something new."

But omotenashi goes far beyond being nice to visitors; it permeates every level of daily life and is learned from a young age.

"Many of us grew up with a proverb," said Noriko Kobayashi, head of inbound tourism atDiscoverLink Setouchi, a consortium that aims to create jobs, preserve local heritage and promote tourism in Onomichi, Hiroshima Prefecture. "It says that 'After someone has done something nice for us, we should do something nice for the other person. But after someone has done something bad to us, we shouldn't do something bad to the other person.' I think these beliefs make us polite in our behaviour."

Japanese people learnt their politeness from an ancient proverb (Credit: Alexander Spatari/Getty)

So where did all this politeness come from? According to Isao Kumakura, professor emeritus at the research institute of Osaka's National Museum of Ethnology, much of Japan's etiquette originated in the formal rituals of the tea ceremony and martial arts. In fact, the word omotenashi, literally "spirit of service", comes from the tea ceremony. The tea-ceremony host works hard to prepare the right atmosphere in which to entertain guests, choosing the most appropriate bowls, flowers and decoration without expecting anything in return. The guests, conscious of the host's efforts, respond by showing an almost reverential gratitude. Both parties thus create an environment of harmony and respect, rooted in the belief that public good comes before private need.

Locals greet you with a bow and a hearty irasshaimase (welcome) (Credit: Wayne Eastep/Getty)

Similarly, politeness and compassion were core values of Bushido (the Way of the Warrior), the ethical code of the samurai, the powerful military caste who were highly skilled in martial arts. This elaborate code, analogous to medieval chivalry, not only governed honour, discipline and morality, but also the right way of doing everything from bowing to serving tea. Its Zen-based precepts demanded mastery over one's emotions, inner serenity and respect for others, enemies included. Bushido became the basis for the code of conduct for society in general.

The wonderful thing about being exposed to so much politeness is that it's as contagious as measles. You soon find yourself acting more kindly, gently and civic-mindedly, handing in lost wallets to the police, smiling as you give way to other drivers, taking your litter home with you and never ever raising your voice (or blowing your nose) in public.

Wouldn't it be great if each visitor took a little bit of omotenashi home with them and spread it around? The ripple effect could sweep the world.

In Japan, omotenashi permeates every level of daily life and is learned from a young age (Credit: Angeles Marin Cabello)

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.