Fr:Ann Nguyen

Ocean Vương, người Mỹ gốc Việt thứ năm nhận giải Thiên Tài MacArthur

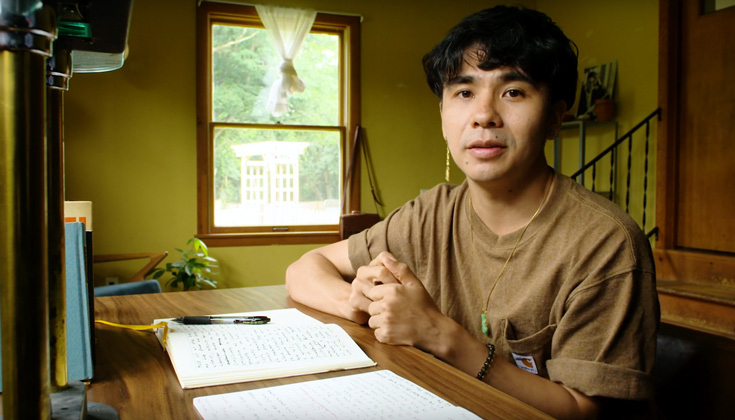

September 25, 2019 Tác giả Occean Vương. (Hình: macfound.org)

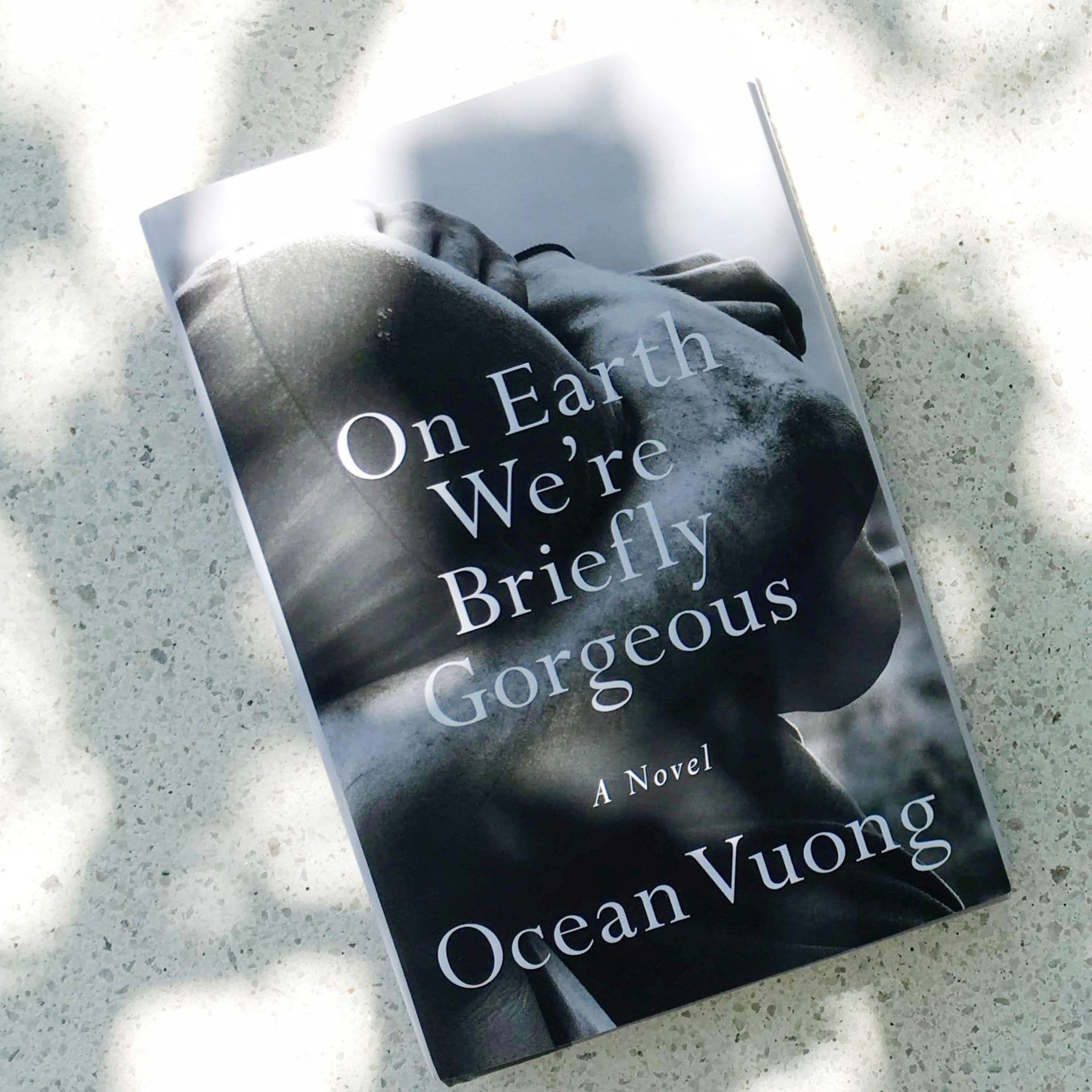

Tác giả Occean Vương. (Hình: macfound.org)WESTMINSTER, California (NV) – Ocean Vương, giáo sư trẻ 30 tuổi người Mỹ gốc Việt tại đại học University of Massachusetts Amherst, vừa được giải Thiên Tài MacArthur “Genius Grant” cho sự sáng tạo phi thường trong các tuyển tập thơ anh sáng tác và tiểu thuyết “On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous.”

Giải Thiên Tài MacArthur “Genius Grant” được tư quỹ John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation thành lập năm 1981. Mỗi năm, khoảng 20-30 người trong các lãnh vực khác nhau được trao tặng vinh dự “Thiên Tài.”

Occean Vương là người Mỹ gốc Việt thứ năm và là nhà văn nhà thơ thứ hai nhận giải “Thiên Tài MacArthur.” Các nhân vật người Mỹ gốc Việt được vinh dự này bao gồm Huỳnh Sanh Thông (1987, thông dịch viên và chủ bút), My Hang V. Huynh (2007, nhà hóa học), An-My Lê (2012, nhiếp ảnh gia), và Viet Thanh Nguyen (2017, nhà văn).

Mỗi thành viên nhận giải Thiên Tài MacArthur sẽ được thưởng $625,000 trong vòng năm năm. Trước 2013, giải thưởng có giá trị $500,000.

Đặc biệt, tư quỹ công bố kết quả một cách bất ngờ và người nhận giải thường không biết kết phút cuối cùng.

Ngay cả Ocean Vương cũng không dám tin anh được chọn. Anh kể với nhật báo New York Times rằng, khi họ gọi để thông báo anh thắng giải thì “Tôi phải chắc là họ gọi đúng người, bởi vì tôi không muốn khóc xúc động rồi để họ nói là họ nhầm. Nhưng sau đó thì tôi đã khóc.”

Tiểu thuyết đầu tay của Occean Vương “On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous.” (Hình: mprnews.org)

Theo nhật báo New York Times, giải Thiên Tài không nhận đơn ghi danh. Các ứng cử viên được hàng trăm nhân vật bí mật khắp nơi trong nước đề cử, và được một ủy ban giấu tên khoảng hàng chục người chọn.

Để được đề cử, các ứng cử viên phải là công dân Mỹ và không phải là công chức chính phủ.

Ocean Vương, tên tiếng Việt là Vương Quốc Vinh, theo mẹ tị nạn tại Philippines trước khi định cư ở Hartford, tiểu bang Connecticut. Mẹ anh theo nghề nail và anh không nói được tiếng Mỹ khi anh vào trường học. Ở tuổi 11, anh vẫn chưa biết đọc thông thạo bằng các bạn cùng lớp.

Tuy nhiên, khi anh bắt đầu viết thơ thì mọi chuyện đều như thay đổi. Anh tạo cho anh một căn cước khác xa với gia đình anh. Là người đầu tiên trong gia đình học đại học, anh được vinh danh là “Thiên Tài” văn học trong xã hội Mỹ, trong khi chính mẹ của anh là người mù chữ.

“On Earth We’re Simply Gorgeous” là một lá thư dài anh viết cho người mẹ mù chữ này, dẫu biết rằng “mỗi chữ anh viết xuống sẽ đưa anh đi xa mẹ anh một chữ,” như anh tâm sự.

Mẹ anh đang ung thư giai đoạn cuối. Anh nói khi biết tin mẹ mang trọng bệnh, mọi chuyện khác trở nên bé nhỏ đối với anh. Hy vọng giải Thiên Tài này phần nào đó an ủi anh. (TMT)

*****

Zen Buddhist poet and novelist Ocean Vuong awarded MacArthur “Genius Grant”

by Lilly Greenblatt| September 25, 2019Vuong is the author of On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, a “loosely autobiographical” novel written as a letter from a Vietnamese immigrant son to his illiterate mother.

Ocean Vuong. Screenshot via macfound on YouTube.

The Vietnamese-American Zen Buddhist poet and novelist Ocean Vuong has been named one of the 2019 fellows of the MacArthur Foundation — the award known as the “Genius Grant,” which honors “extraordinary originality.”

Vuong, 30, is the author of On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, a “loosely autobiographical novel” written as a letter from a Vietnamese immigrant son to his illiterate mother. Vuong is the child of illiterate rice farmers from rural Vietnam and came to the United States as a refugee with his family when he was two. As the MacArthur website reads, his poetry is “infused with the rhythm, cadences, and imagery of rural Vietnamese oral storytelling and folkloric traditions married to a restless experimentation with the English language.”

The MacArthur fellowship “genius grant” awards recipients with $625,000 to be distributed over five years. Vuong is one of the youngest fellows chosen this year, alongside 30-year old artist Cameron Rowland.

In a video posted by the MacArthur foundation announcing Vuong’s fellowship, he speaks to his Zen Buddhist practice.

“In my Zen Buddhist practice, one of the most privileged state of minds is not the expert, it’s not the master, it’s what’s called the beginner’s mind,” says Vuong.

“The beginner’s mind is a mind that approaches the natural world, and the phenomenas within it, with utmost curiosity. And I think one of the most perennial powers of an artistic mind is awe and wonder before the world,” he says

Vuong is also the author of poetry chapbooks Burnings and No. His first full-length collection of poetry, Night Sky with Exit Wounds, was published in 2016. He is currently an assistant professor in the MFA Program for Poets and Writers at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Ocean Vuong, Poet and Fiction Writer | 2019 MacArthur Fellow

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SH1Y-KpRhoY&feature=youtu.be

*******

Interview

Ocean Vuong: ‘As a child I would ask: What’s napalm?’

Emma BrockesThe ObserverHow did a Vietnamese refugee come to write what many are hailing as the great American novel?

While he was an undergraduate, Ocean Vuong formed the habit of writing at night. During the day, he studied literature at Brooklyn College and worked in a cafe. At night, he stayed up writing poems. It wasn’t just the sense of isolation that comes from being the only one awake, when “you look out of the window and it’s completely dark and you’re at sea in this little ship”. It was more that writing in the off-hours relaxed his knack for self-criticism. “You get the last word of the day,” he says. “The editor in your head – the nagging, insecure, worrisome social editor – starts to retire. When that editor falls asleep, I get to do what I want. The cat’s out to play.”

The poems that came out of those night-time efforts were published in 2016 as Night Sky With Exit Wounds, the success of which still amazes the author – the book won a Whiting award that year, and in 2017 scooped both the Forward prize and the TS Eliot prize. Vuong, who is 30, was not from a background from which writers traditionally emerge. As a two-year-old, he had been brought to the US from Vietnam as a refugee and settled with his family in the working-class town of Hartford, Connecticut. No one in his family spoke English. When his father left, his mother got work in a nail salon, menial work for little reward and a quality of life that Vuong had no particular expectation of exceeding. If Night Sky tackled the absent father as myth, then his debut novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, reckons with the mother and grandmother who raised him and it is the influence of these women – courageous, difficult, devastated by the ripple effect of the Vietnam war – that forms the spine of the novel and asks the central question: after trauma, how do we love?

We are in Vuong’s open-plan living room in Northampton, Massachusetts, a leafy college town where he teaches creative writing at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Peter, his partner of 10 years, has taken the dog out. Vuong is slight, with a silver earring in one ear and the habit of pushing his tortoiseshell glasses up his nose. He speaks, as he writes, in poetic imagery, what he calls “the metaphor as autobiography of the gaze”. In the novel, the world seen through a speeding car window “surges by like sidewise gravity”. A bird on a windowsill appears not as a bucolic symbol but “a charred pear”. To Little Dog, the protagonist – so named by his family to protect him beneath a cloak of worthlessness – the world is an ugly place, in which beauty is made more so for the improbability of existing at all. “Freedom,” he says, “is nothing but the distance between the hunter and its prey.”

That On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous is one of the most anticipated novels of the year – the novelist Max Porter has called it “staggeringly beautiful”, observing that “it seems obvious now that a gay young poet born in Saigon would write the great American novel” – is, in large part, down to its perfect engineering, a piece of autobiographical fiction that avoids all the traps of that genre. It is fluid, moving the way thought moves, in circles not lines, and written in the form of a letter to Little Dog’s mother that he knows she’ll never read. It is easy to imagine a bad version of this novel in which any one of its preoccupations might have overgrown to capsize it. It might have been the Opioid Novel, or the Vietnam Novel, or the Exploitative World of the Nail Salon novel. It might have been the Gay Adolescent Love novel or the Violent Childhood novel, all themes that are touched upon lightly while still assuming a fully weighted presence in the narrative. How Vuong does this is a mystery, as is the seamlessness with which he moves between scenes of violence in the Vietnam war to scenes of violence in the home in Connecticut, to love scenes with a doomed boy called Trevor. The book has a poetic density that is at once elliptical and unflinching in its gaze, a testimony to the endlessly complicated dynamics of damage. “Sometimes being offered tenderness,” writes Vuong, “feels like the very proof that you’ve been ruined.”

Vuong grew up in a world in which he was marginalised across every axis – class, race, sexuality. His was a violent household. In a memoir piece he wrote for the New Yorker two years ago, which would form the basis of many scenes in the novel, Vuong, addressing his mother, recalled “the time you hit me with the remote control. A bruise I would lie about to my teachers. I fell playing tag.” And,“the time you threw the box of Legos at my head. The hardwood dotted with blood.” And, “the time with a gallon of milk. A shattering on the side of my head, then the steady white rain on the kitchen tiles.”

Post-traumatic stress disorder was something no one had any idea about at the time, “except in veterans”. But there is no question, looking back, that both his grandmother, who saw her village in Vietnam razed by US soldiers, and his mother, ripped from everything familiar for a new life in the US, where her husband beat her before leaving, were suffering from PTSD. Violence was the ugly expression of this trauma, but with distance, Vuong could see a positive release of that energy, too – chiefly in the way that his mother and grandmother told stories.

“I didn’t know this until I talked to other Vietnamese-Americans – that it was rare for families to talk about the war,” he says. Partly it came out of boredom. They were broke, stuck in the house with each other and “we had no TV”. But there was something else going on, too. “The stories, at first, were folklore. My grandmother would tell a ghost story, then she would say: oh, that was after the napalm. So through cycles of these stories, that world started opening and as a child I would ask: what’s napalm? They ploughed on. It was almost intoxicating for them to create a mythology of their lives, because they were so powerless. They were all women. The men were gone; they did their harm and were gone. And they were empty hands, had no English, were powerless everywhere else. But when it was time to tell the story, they held everything.”

Vuong had no context for what he was hearing. He only knew that in the stories, these women who counted for nothing outside, ran through the fire and survived. “They turned themselves into myths and it had a rhetorical power. They turned themselves into the Odyssey.”

In the novel, the trauma of Little Dog’s mother and grandmother shines through in grimly humorous ways. Lan, the grandmother, yelling at his addled mother to get back in the car, shouts to get through to her, “get back in the helicopter”. Buying a dress from the Salvation Army, his mother asks Little Dog to read the label and find out, “is it fireproof?” In the family mythology, Vuong was the single last hope of these indestructible women and when, in the mid-2000s, Hartford was hit by the opioid epidemic, it’s the thing that stopped him from leaning towards drugs. “A lot of my friends were dying. And I thought: OK, I can die.” Worn out by poverty, bullying, bereavement and violence, he regarded this outcome as regrettable, but “I think that might not have been enough, were it not for me being my family ’s only hope. Because they were also dying, in a different way: financially, mentally. And I thought, I can’t die. Literally I can’t die.” He wanted to change his family’s story. He wanted to make his mother happy. He wanted to exceed the expectations of someone born to his station in life.

So what did he do?

He smiles. “I went to business school.”

There was a year in early adulthood when Vuong and his mother didn’t speak. He knew life had been hard for her, leaving Vietnam and dealing with his father, about whom he knows very little other than that after his mother kicked him out, he “went off to do criminal things and ended up going to jail”. But he hadn’t yet got to the stage of forgiving her. “It was the worst, for both of us,” he says. “And when we looked at each other again, we just sobbed and said: oh, we can’t do that. We’ve got to find a way.” This happened before Vuong had written a single line, and it was important; “a pivotal moment to understand that anger destroys, not only those around you, but especially yourself. Anger is energy – you can get a lot done with anger; you can write multiple books. We’ve read those books and you realise as you’re reading them: oh, this is not for me. It’s their own project. So I didn’t want to write angry. I didn’t want to be angry. I saw what anger did, growing up, and it was powerful, a force to be reckoned with, but it didn’t lead to anywhere that I was interested in going.”

This isn’t the received wisdom among many of those applying to study creative writing at college, where it is sometimes assumed that having something to rage about is a definite advantage. After eight weeks at business school – which he characterises as “learning to lie” – Vuong dropped out and enrolled to read literature at Brooklyn College. He started to write poetry. And then he had an unsettling experience.

Freshly arrived in New York, he turned up at a poetry reading one night, pretty sure he was about to “meet my people”, having spent the previous two decades as a fish out of water. “And the first thing someone said to me was: hey, I’m at Sarah Lawrence, where are you studying? And I said: oh, I’m not in an MFA [master of fine arts]. And he just turned around and walked off.” He bursts out laughing. “It was amazing.” Another student on a prestigious writing programme chatted to Vuong for a few moments, before saying: “You’re so lucky – you’re gay and from war.”The idea of Vuong’s childhood as a generator of great material for fiction is one that makes him laugh like a drain. These days, if any of his upper-middle-class students grouse that they don’t have a good backstory, he mildly points out that Virginia Woolf got one of the best novels ever written out of someone basically crossing a lawn. At the time, however, he was shocked and disappointed. He hadn’t been prepared for the merciless competition of the New York poetry crowd “which depended on appearances, soirees and parties. So I just holed up in my apartment and the library.” His confidence cratered. He wondered if he’d made a terrible mistake. Then he hit upon an unexpected remedy. “A huge moment in my education as a writer was reading biographies. I beg my students to do it, because everything that they’re feeling, Sylvia Plath felt 70 years ago. And Ginsburg and Lorca and Rimbaud. There’s Virginia Woolf, this genius, who’s going on a crisis walk. You read the prose and you would never think this woman has any doubt. And yet here she is, out there, asking: what am I doing?”

Vuong thinks he was lucky in some ways. “I had no pressure. I could really experiment with my voice. I could play, and find pleasure in it. I see with my students that they’re under a lot of pressure from their families. A parent will say to me: “my future Pulitzer winner!” and I just groan. Poor kid. What do you say to that?”

He started going to open mic poetry events, which were shabbier and more democratic than formal readings, and at one of which he met a law student called Peter. To that point, Vuong’s relationships had been largely dysfunctional, “bad, bad relationships in almost this cliched trope of seeing what’s familiar in violent, self-destructive folks”. His horizons had been limited in other ways, too. It is an odd side-effect of poverty that you become trapped in a previous era, he says; new things take longer to arrive, and when they do, no one has time to absorb them. “You don’t have no time. That’s the thing everybody in my community says: I ain’t got no time for that!” He laughs. “Being poor is about waiting, I learned. You’re waiting in line for welfare. You go to the ER, you wait. You want to file for sexual assault? You wait. And so everybody’s in a queue and one thing that happens is that you’re in a cultural time warp. You’re in the past. So when I went to New York in 2007, I had no iPhone, no Facebook; in my community, when it comes to technology and access, they are mostly in the late 90s.”

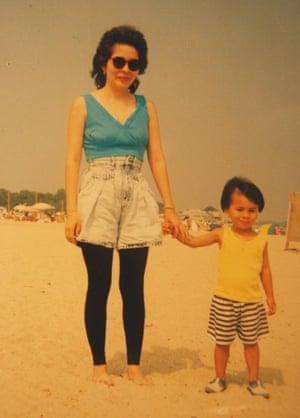

Ocean Vuong and his mother.

They were also culturally fairly regressive, although in his own home at least, homophobia was one of Vuong’s lesser problems. (There is a heartbreaking bit in the novel in which Little Dog wakes to find “FAG4LIFE” scrawled on his family’s front door in red paint and he tells his mum that it reads: “Merry Christmas, Ma. See? That’s why it’s red. For luck.”) When he was growing up, his mother and grandmother weren’t thrilled by his sexuality, but “because they came from a long line of rice farmers, they were close to native traditions in Vietnam, and those communities had intersex folks who were seen as having all-seeing power. They were powerful people and there was a mysticism associated with that. That doesn’t mean they hoped their children would be queer. But although they were shocked, they had a very practical way of looking at things. That’s what I admired about them. Their view is that this is borrowed time. We should’ve been gone up in smoke. But now we’re here, let’s just live.”

The downside to this attitude was economic ruin. “It leads to financial woes and bankruptcy. Maxed-out credit cards.” He’s laughing now. “OK, after 20 years, the party’s over! Let’s think about savings! They’re all in financial ruts because they had that mentality.”

It was a joyfulness, or at least a somewhat constructive outlook, that Vuong associates with women who emerge from trauma as opposed to destructive and self-destructing men. It still amazes him, looking back, how the women in his family – his mother, his grandmother, his aunts – dealt with the threat of their husbands. “The incredible thing that I can never quite understand was how they were able to kick them all out. The men had access to jobs, money, a patriarchal presence in the world, and even though they had troubles too, as immigrants and refugees, we come from a patriarchal tradition in the old country just as deeply rooted as in the west. In some cases, when men are talking to each other, women aren’t supposed to even be in the room. So that was what they were coming out of. And to think divorce?! These things were still taboo where they came from. And they all really did it.”

The question of courage underlines everything Vuong writes, both in terms of the characters and in the nerve held by the writer creating them. Night Sky With Exit Wounds, published when he was 27, and which “took off in ways that no poet ever suspects will happen, and should not expect again”, dared to imagine scenes in which brutality and sensuality combined. (In one scene, the poet describes his father masturbating in a bathroom after he has beaten his mother, observing “that a man in climax is the closest thing to surrender”.) The novel has a similarly shocking breadth of sympathies. In both, Vuong’s ultimate aim was to dignify the experiences of his childhood with the solemn, years-long gaze of the novelist.

“The great male writers of the European tradition, be it Proust, Tolstoy, Turgenev, deemed that those most inspiring to them existed in a white aristocracy,” he says. “You read those books and you wouldn’t even know that people of colour existed in Europe. To each his own, and that was their choice. But I wanted to say: these lives, of women, and even of poor white people – these lives are worthy of literature. As Turgenev looked at the crumbling Russian empire, I look at these folks in a different crumbling empire and deemed that these are inspiring lives to an artist.”He also wanted to say something about where the cost of war falls, not from the vantage point of the grand historical epic, but from inside the small, cramped sadness of a house still flattened decades after the conflict has ended. “It’s the stories of our species that men create these wars and women clean them up. They clean them up emotionally, they have to deal with the PTSD that comes home, they have to postpone their own healing, forgo their own self-care, in order to hold these households together. They literally nurse these broken bodies back to health. I wanted a book to honour that without romanticising it. To say women have been doing this and they’re not necessarily these heroic legends. What’s the mental cost of the women who do these extraordinary things? In the book, the cost is their own private life.”

A few months ago, Vuong’s mother was diagnosed with stage 4 breast cancer and he has been commuting back and forth to Hartford to accompany her to chemotherapy. After a dire admission to hospital, during which, he says, she was in so much pain “it sounded like warfare and I was ready to bury her”, she is responding to treatment and even hopes to come to his book launch. He thinks of something she said to him when he first left for New York. “She told me: it’s OK for people to think you’re a fool.” Vuong laughed and said: “Really? Why?” and his mother replied: “Because then they’ll tell you everything about them. You can see them from all their angles.” It’s the wisdom of his life. The subversive power of being “a small, queer, person of colour” is that Vuong has the ability to see everything. He smiles. “Nobody hides themselves from a fool.”

• On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous is published by Jonathan Cape (£12.99). To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £15, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99